Managers in enterprises or start-up founders all have to go through a framework in order to unlock the necessary investment for their blockchain projects. Understanding that process and what it entails is key. Areiel Wolanow is managing director of Finserv Experts, expert advisor to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Blockchain amongst many other blockchain advisory and non-exec positions. In this podcast he takes us through the commonalities between successful and failed blockchain projects before building a framework for requesting investment for a blockchain project.

What is blockchain?

Blockchain is an enabling technology. It allows multiple separate legal parties to share a single version of data and keep that data in synch between themselves. Thus, removing the need to reconcile different versions of data between themselves.

Journey to blockchain

In early 2014, Areiel was running IBM’s financial services practice for East Africa based out of Nairobi. 90% of the Ethiopian commodity exchange is with coffee. The challenge that they faced was that the Fair Trade Association was threatening to remove accreditation across the country, because of the level of corruption. Virtually all coffee farmers in Ethiopia were calling themselves Fair Trade with only a tiny minority having actually gone through the process.

The Ethiopian commodity exchange had asked IBM if they could do an IOT based provenance solution. The idea was to give where farmers, who had gone through the Fair Trade process, the ability to purchase Fair Trade RFID tags to put in their coffee bags. Whilst this solution would help solve the problem from the farm side, the problem remerged when the coffee reached the roaster and ultimately the market floor. The Fair Trade coffee would get mixed with other coffees thus making the ability to trace provenance very difficult and easily gamed.

It became clear that considering these challenges that blockchain could be an excellent solution for nailing down the provenance, tracking the coffee throughout the various transactions all the way to the consumer scanning a QR code on their coffee bag and seeing their coffees journey.

Blockchain – addressing the “world’s oldest business requirement”

The above coffee example, or Everledger with diamonds, demonstrate how provenance is a powerful use case for blockchain.

Blockchain is an innovation that addresses what Areiel refers to as the “World’s oldest business requirement”. This is a requirement that goes back to 4,000 BC when humans were designing the very first contracts.

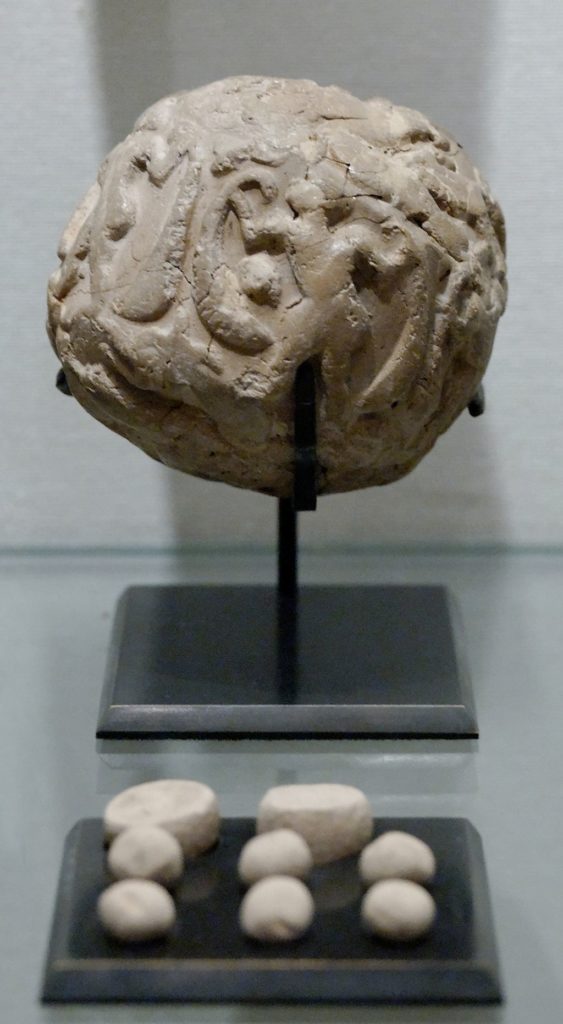

A bulla (or clay envelope) and its contents on display at the Louvre. Uruk period (4000 BC–3100 BC).

At that time Sumerians would record future commitments (eg. use of an Ox for bushels of grains) on a “bulla” a hollow ball-like clay that contained tokens that identified the quantity and types of goods being recorded. This ball would provide an independent verifiable tokenised representation of a contract. A bulla was at that time as transformative as the internet is today.

However, as the bulla becoming increasingly adopted it became difficult for individuals to remember how many tokens where inside each balls. This set an upper limit on scale of the bulla system. The next invention was creating indentations on the outside of the bulla to represent the number of tokens on the inside. These indentations eventually took the form of symbols to represent not just the number of tokens but the different type of tokens.

Finally, it was realised that the symbols had supplanted the tokens themselves. As long as both parties where present when the symbols were being drawn and that they were accurate, there wasn’t any more a need for tokens.

Ultimately the move came from this clay ball to the use of cuneiform script, the oldest form of writing, which developed out of the need to model future commitments. Cuneiform writing become an independently verifiable record of that commitment, now known as a ledger. A thousand years later cuneiform script would eventually be used not just for writing contracts but also for law, politics, religion, philosophy, music and literature.

Blockchain is just the latest step in this journey of maintaining ledger.

Blockchain in numbers

There has been up to now about 80,000 blockchain projects around the world. This includes start-ups, enterprise POCs and pilots, and crypto related projects. 92% of them have already failed which is broadly in line with the 90% failure rate of most start-ups.

A McKinsey report called “Blockchain’s Ocam problem” stated “The bottom line is that despite billions of dollars of investment, and nearly as many headlines, evidence for a practical scalable use for blockchain is thin on the ground.”

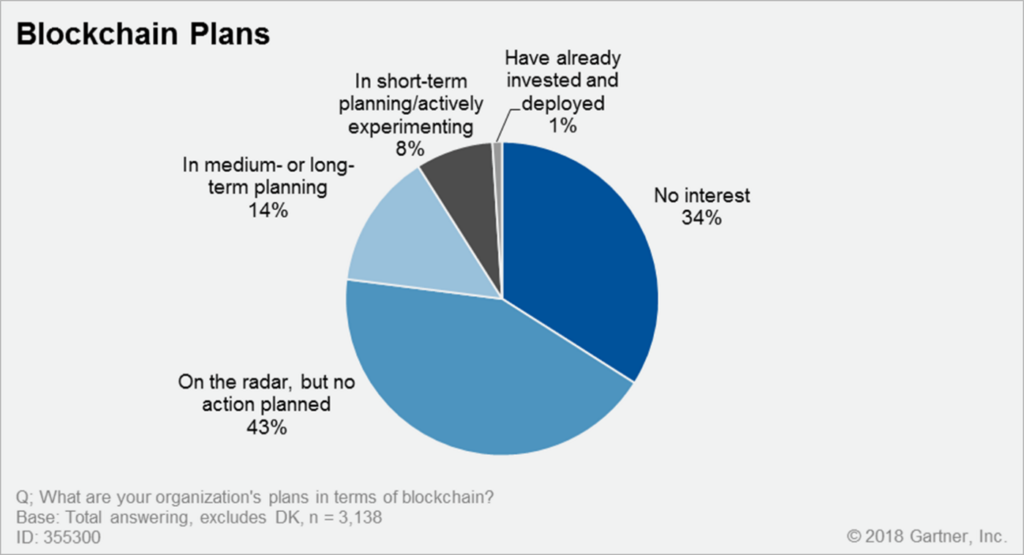

77% of CIO’s surveyed by Gartner at the “Gartner 2018 CIO Agenda at Gartner Symposium/ITxpo 2017” stated the blockchain didn’t even feature on their radar. A PWC 2018 survey of 600 executives from 15 territories, state that 84% say their organisations have at least some involvement with blockchain technology.

For Areiel, what this indicates is that the push to adopt blockchain isn’t coming in from IT but from the business. Most blockchain developments are being sponsored by the business and not by IT. It is being delivered by external development centres. They’re not being done at the enterprise level but at a line of business level. So, if a head of a line of business is developing a blockchain project it won’t show up on the CIOs radar or even on the enterprise architecture level. The stats from CIOs survey and the McKinsey report aren’t inconsistent with where the money is being spent and at what level within the organisation.

It’s the line of business leaders who are spending on blockchain which are benefiting from it.

What are the characteristics of a successful or failed blockchain project?

A lot of blockchain project are sold under the promise that it will deliver numerous benefits for a consortium. However, it assumes that the network reaches critical mass and thus all participants will automatically sign up to the network in the hope of reaching that shared benefit.

Areiel states that one of the first due diligence rules he has in place is to say that “if your business model doesn’t produce a substantial ROI of at least 20% or more for the very first user of the network, stop!” Adoption is critical to get a network going.

So you need great value for the first adopter. Additionally, you need a solution for people to be sharing the ownership of their data.

Big food retailers like Tesco have become the de facto regulators. Their regulations are more strict and more enforced than government regulations around food safety. For example if you run a chicken farm and one of your chickens has salmonella then you will be fined about £30k by the government. If Tesco finds out you’re out of businesses. Tesco has more clout in enforcing food safety. Tesco has a complete lock on the supply chain, thus it doesn’t need a blockchain. It can force its suppliers to give it their data onto their database which they own. There is no benefit for them to have decentralised database model as they can mandate a centralised one which they have full control over.

Cost of measuring existing process vs blockchain process

Areiel, alongside Charles Ayorinde from AXA and Richard Boreham from ChainThat where tasked to work on a feasibility study for a DLT based trade settlement and claims agreement for Lloyd’s as part of the LM TOM programme. They had to answer two questions:

- Is it possible to conceive a business model for running both Lloyds and company market business without the need for a bureau?

- If so what is the economic case for doing that, be?

“Operations research” in 1960s and 1970s were the hot topic of business schools. It is a discipline used to measure the cost of doing business within a certain business process. They used that process to develop the business case for Lloyds, the result of which demonstrated that the business case was very strong.

In Areiel’s view the strength of the business case was centred around the core value proposition of blockchain, a ledger. Lloyd’s and the company’s market spend a significant amount of money, time and effort keeping insurance contracts in synch between all the different partners instead of primary value creation. Lloyd’s expense ratio is one of the highest in the world. The existing business processes for settling and claims agreement where first codified in 1810 and haven’t changed much since then.

The idea of a solution that removes the need for a centralised transaction processing capability is huge. But even outside of Lloyd’s or placement of syndicated risks, you are seeing tremendous benefits. Blocksure, a blockchain development company, is working with insurance companies providing them with significant cost reduction opportunities for new line of business compared to what it would cost to launch with traditional processes. See Insureblock’s podcast of Blocksure with Commercial General.

Blockchain with new lines of business

Start your blockchain journey with a new line of business, new products or new customer segments. This is where you should see the first changes. The reason is because neither you nor other members of your trading network have to worry about transformation costs. Starting with a new line of business removes the need for transformation costs.

Delivering micro insurance for natural disasters in Indonesia. Only 6% of Indonesians have insurance because the cost of placing it makes it unaffordable and regressive.

In parts of Indonesia the only way to pay a claim is to send someone out on a helicopter with a suit case of cash which if it is a small amount of money the cost of the helicopter trip is higher than the claim.

With blockchain you can pay claims into a mobile wallet in addition to managing the operational costs of doing the placement.

Framework of thinking for requesting investment in a blockchain project

Present the benefits in a manner that someone understands and be able to quantify them. For example how long does it take to produce a D&O policy, how long does it take to send all the emails, and to reconcile our version of documents for example.

At Lloyd’s, one of the biggest drivers of additional costs in processing an insurance contract or in agreeing a claim is the cost of a query. A question somebody has to ask before making a decision. That brings the entire process to a halt. Queries happen because data isn’t kept in synch. In the feasibility study, Areiel and his team measured how much time is spent handling queries, what percentage of transactions have queries, how many full time employees spend their time processing queries. This provides a basis on which to extrapolate. In addition they ran a simulation based on the answers they were given and used that to estimate the cost of reduction.

Workshop

The workshop is called “Unlocking investment in blockchain projects”, it’s a 3-hour course in introducing this framework of thinking on how to present the business benefits of a blockchain project in a way that investors can consume. If you’d like to find out more about this workshop you can click here.

Your Turn

Thank you, Areiel, for sharing your insights on unlocking investment in blockchain projects. If you liked this episode, please do review it on iTunes. If you have any comments or suggestions on how we could improve, please don’t hesitate to add a comment below. If you’d like to ask Antony a question, feel free to add a comment below and we’ll get him over to our site to answer your questions.