Cindy Vestergaard is the Stimson Centre Director, Nuclear Safeguards Program & Director, Blockchain in Practice program. In this podcast we discuss the interesting work she does in safeguarding nuclear material with blockchain technology.

What is blockchain?

Blockchain is a subset of DLT, which is essentially a combination of a variety of different technologies that have been around for already a number of decades, such as peer to peer protocols, cryptography hashing, to make it an immutable ledger that can be shared securely, digitally, across the ecosystem.

The Stimson Centre

The Stimson Centre is a think tank that was set up in 1989 by Barry Blechman & Michael Krepon at a time when the Cold War was ending shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall. It’s a nonpartisan and independent centre that looks at real world problems.

The work that Cindy’s team does is evidence-based policy research that sits at the intersection of technology and policy.

SLAFKA

In 2019 a partnership was established between the Finnish Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (STUK), the Stimson Centre in Washington, D.C., and the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, Australia, to develop the world’s first distributed ledger technology (DLT) prototype for safeguarding nuclear material, called SLAFKA.

Finland is the first country in the world to be building a deep geological repository for its spent nuclear fuel. STUK, its radiation and nuclear safety authority approached the Stimson Centre for helping them develop a prototype.

The question for STUK and for the government of Finland needed to answer is how to ensure that the material underground is also the same that is reflected on the books above ground. Data integrity is very important. The other reason is concerning their relationship with Euratom, the regional safeguards body for the EU’s member states that ensures a regular and equitable supply of nuclear fuels to EU users. The objective is in increasing security, enhancing data sharing and transparency between STUK and Euratom.

For the Stimson Centre, the opportunity, was to see if DLT can actually handle the different types of transactions that are needed under a nuclear safeguards agreement.

Data transactions and trust amongst parties

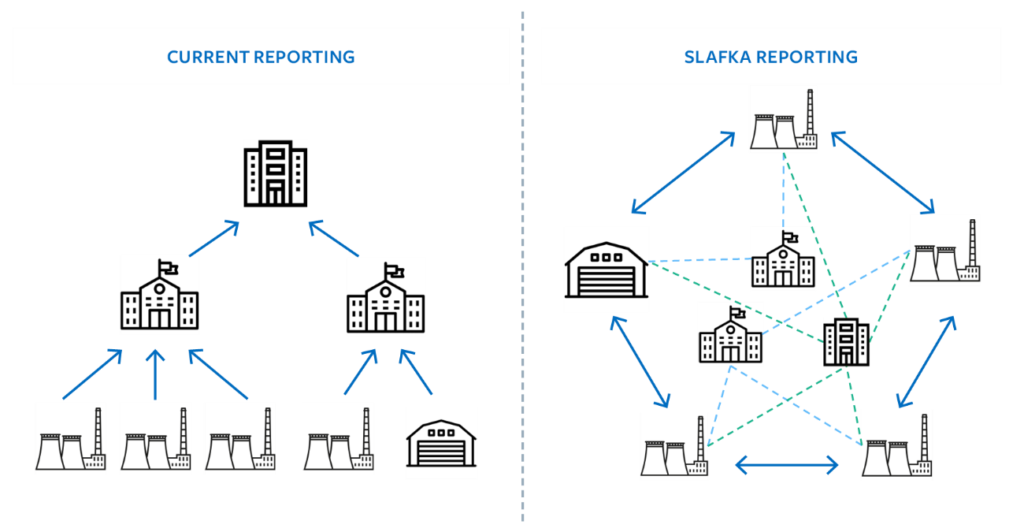

From a data transaction perspective; nuclear material moves within a facility, within a country and internationally. As it moves it also shifts in form for example from yellowcake or uranium ore concentrates to enriched uranium. All these movements and change of state have to be logged and reported to either a national regulator or a regional regulator such as Euratom within the EU and then to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna.

Today’s data transactions come in all shape and form both in terms of paper and in an electronic format. The IAEA has a portal for safeguards declarations but it isn’t universally used. Some countries still provide their declaration on a USB stick whilst others on paper.

In the nuclear world there isn’t a lot of trust among different parties. The IAEA goes in to monitor and verify that what states are doing is actually meeting their obligations in using nuclear material for peaceful purposes.

One of the reasons why the IAEA hasn’t launched a blockchain system is partly due to its stage of digitisation. International organisations such as the IAEA are the still the product of their member states. If member states are not willing to put money in certain thing then it takes a long time for them to happen.

Launch of the Proof of Concept (PoC)

On the 10th of March 2020 the SLAFKA PoC was officially launched in Helsinki. The purpose of the PoC was to demonstrate can the DLT SLAFA prototype handle nuclear safeguard transactions? The answer was yes. The platform was able to demonstrate transactions:

- Shipping material within a country or outside of a country

- Related to a deep geological repository

- Type Code 10, EU regulation 2004 known as the Commission Regulation (Euratom) No 302/2005 of 8 February 2005 on the application of Euratom safeguards agreements with the IAEA which are based on the nuclear non proliferation treaty

They did not test the security side of things as they wanted to focus on transactions.

Hyperledger Fabric

As Hyperledger Fabric permits different roles for different members and different access in terms of read and write restrictions, this aligned well with the confidentiality aspects related to nuclear material.

In SLAFKA the chain code allows them to build access controls. For example, in a domestic shipment it would check whether the peer proposing it is within a list of approved holders. Holders of nuclear materials or nodes that have the permission to transact that particular batch of nuclear material. There are a number of different confidentiality rules that come with nuclear materials. A nuclear operator for example, such as a nuclear plant can see its own inventory on SLAFKA, but can’t see the inventory of another nuclear operator. The regulator has full access whilst the IAEA has its own range of access controls at an international level.

Next steps for SLAFKA

SLAFKA is a first step that will not be commercialised as it is for demonstration purposes only. SLAFKA is open and transparent to demonstrate and educate different stakeholders within the nuclear fuel cycle on the usage of DLT.

DLT is a disruptive technology, however SLAFKA has to demonstrate that it isn’t going to mess with certainty that nuclear material is not misused or diverted for nefarious purposes. That it isn’t going to mess with the governance structure, the international treaties, the requirements and obligations that are currently established.

Next Steps for SLAFKA:

- Test further safeguard transactions in addition to the one related to Code 10 but ones under the “Additional Protocol”.

- A system of Nuclear Cooperation Agreement (NCA) which are bilateral trade agreements between states, usually a prerequisite before they can trade in nuclear material. And those agreements will also have specific reporting requirements, and to share information specific to the trade of that nuclear material or technologies. Countries like the United States, Canada or Australia can have nuclear cooperation agreements upwards of 20 – 30 different types of agreements. Being able to have that information in a more efficient ledger would be one area to test.

- Transport security

- Export controls

Exploring expanding SLAFKA beyond nuclear to the chemical. There are a lot of similarities in international treaties when it comes to non-proliferation. The Chemical Weapons Convention is for disarmament of a category of mass destruction. Under that agreement states have to fully disarm and of course, there are a number of reporting requirements that dwarf the nuclear material space.

The Stimson Centre has a proposal for which they hope to receive funding for them to work with the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons on that. There they are looking at what’s called scheduled chemicals under the CWC (Chemical Weapons Convention), specific chemical that have to be reported in terms of their international trade.

Throughout this process, Cindy hopes to be able to provide a comparison, of their different types of DLT prototypes to show the different lessons that they can learn from them when it comes to not just nuclear, but also chemical non-proliferation, hopefully, also biological non-proliferation, and then she hopes to also getting into small arms and light weapons, and so on and so forth.