Chris Ballinger is the CEO and founder of MOBI – the Mobility Open Blockchain Initiative. MOBI is a non-profit smart mobility consortium working with forward thinking companies, governments, and NGOs to make mobility services more efficient, affordable, greener, safer, and less congested by promoting standards and accelerating the adoption of blockchain, distributed ledger, and related technologies in the mobility industry.

About Chris Ballinger

Chris started out in monetary economics and worked briefly for the Council of Economic Advisors in the United States. Chris moved into Fintech in the early days of the derivates market. More recently he joined Toyota as the CFO of their financial service organisation, the same year that Lehman Brothers went bankrupt.

Whilst at Toyota he eventually went on to work at the Toyota Research Institute, which is Toyota’s arm in Silicon Valley that does the development of autonomous vehicles and robotics and AI.

Whilst he was there, Chris developed his thinking on new mobility services and how blockchain and distributed ledger’s might be able to improve the new mobility service economy. Two years ago, Chris left the Toyota Research Institute ,and launched along with others MOBI.

What is blockchain?

Blockchain is a particular kind of distributed database that is append only where the rules for appending blocks are designed to make sure that the information is agreed on by the participants.

But more generally, blockchain is common usage, it’s a broad collection of technologies, including cryptography, open databases, payments, perhaps identity, and probably quite a few other things.

Blockchain’s potential for redefining the automotive industry

For Chris blockchain and related technologies broadly bring four unique capabilities to the table:

- Digital twins: bringing digital identities to physical things.

- Micropayments: Today’s banking system is relatively expensive as is the variety of other trust services related to payments. By reducing the cost of those trust services and enabling peer to peer payment, the size of the payment you can do goes down. Once that goes down you can pay for more things with micropayments, thus enabling things that aren’t monetizable today to become monetizable. That may include the buying and selling of data from a car. Charging for city infrastructure in small increments for congestion pricing, pollution pricing, carbon footprint pricing and all these kinds of things might become possible with lower overhead costs for payments.

- Trusted shared data. When Chris was the CFO at Toyota, most of the financing was through securitization. Securitization, is the main financing mechanism for vehicles where a collection of auto loans get sold off to third parties. The overhead costs for that process, such as legal fees, accounting fees, reconciliation fees and trust are 1 to 2% of the value of the loan. Being able to have an open database that everybody can look at, share and agree as the single source of truth can potentially reduce the cost for transacting quite a bit.

- Data privacy and protection – the ability to control user data or third-party app data at its source, instead of it being shipped to a central database where it can be a single point of attack.

These are the four basic capabilities that blockchain can bring to the mobility industry. They can be combined in various different ways to create a lot of interesting use cases.

For Chris the single most interesting one is the ability for vehicles to pay as they go for things.

The combination of blockchain, IoT and AI that gives anything that is connected with a modicum of sensors and intelligence, the ability to have an identity, act intelligently and autonomously in its ecosystem, and to participate in an economy autonomously. With respect to vehicles what that means is vehicles moving around and being able to interact with their environment as economic agents.

How MOBI started? – the Mobility Open Blockchain Initiative

MOBI grew out of a bunch of individuals doing proof of concepts (PoCs) on blockchain and distributed ledgers within their own companies. At that time Chris was at Toyota and had been running a number of small projects from 2015 to 2017 around digital twins, vehicle wallets, ride sharing on a blockchain, and car usage-based insurance and monetizing data.

As all these individuals started talking they realised that they were all doing the same PoCs in their respective auto companies. The common problem they faced wasn’t one of technology but of getting to scale. How do you reach a tipping point using a new technology so that it becomes logical to adopt it? Nobody had a good answer for that.

After a few meetings first under the auspices of the Digital Currency Initiative at the MIT Media Lab and then later at Silicon Valley the group grew and grew until there were 50 or 60 people in the room from a lot of different auto companies and a bunch of start-ups and tech companies. The participants agreed there was a need to formalise the meetups into an organisation to promote the use of this technology and particularly to develop standards.

Chris clarifies that by standards he means simple things such as how transactions are accomplished, how payments are made, how vehicles are identified, how they identify infrastructure, how they present themselves to infrastructure. These “standards” aren’t too different to those made a hundred years ago when the first autos arrived on the road and decisions had to be made on whether a vehicle travels on the left or right hand side of a road.

The participants realised there was a clear need to develop those standards, as standards are an important part for reaching scale. One of the participants had to quit their day job to run this organisation and Chris volunteered for the role. That was two years ago.

Today MOBI is a non-profit consortium. It’s a group of companies that have gotten together with a shared interest in developing this technology. They realised that they can’t do it on their own and decided to launch MOBI. MOBI’s mission statement is to use these technologies to make mobility, greener, safe and more affordable.

The role WAYMO and autonomous driving?

Chris’s old boss at the Toyota Research Institute was Gill Pratt who was the project manager for the DARPA Grand Challenge. Gill informed Chris that autonomous driving is going to take a lot more data than people think. It’s going to take machine learning an awful lot of edge cases to understand autonomous driving and the only way to get the relevant edge cases is to collect an awful lot of miles, about half a trillion miles. That was more miles than any car company was accumulating. Even WAYMO who at that time was doing a million miles a month would have taken centuries to reach half a trillion miles.

A report by the RAND Corporation states that “Autonomous vehicles would have to be driven hundreds of millions of miles and, under some scenarios, hundreds of billions of miles to create enough data to clearly demonstrate their safety”

As Chris states – if you think about data and the economics of data there is some interesting points regarding it. When you share data with somebody, regardless of what the contract may say, the sharing entity probably lose control over it. Data is free to copy. Thus, if you share data to somebody else it loses value because it gets out into the wild. If that is the problem for everybody then nobody shares.

Monetization of data isn’t through sharing but by keeping it protected in a silo with the incentive being to try and collect the fastest and most amount of data in order to becoming a monopolist before anybody else does.

The problem of autonomous driving is, to a large extent a problem of accumulating enough data to run your machine learning algorithms.

Gill Pratt asked Chris if blockchain could help car companies to share data in ways that they couldn’t. Was there a way for federated machine learning where the data can stay in its own location, where the algorithm can go to the data and still allow it to learn but in a way that avoids the data market failure.

Chris found Gill’s question interesting and whilst researching that question it led Chris to Trent McConaghy and Bruce Pon (who both appeared on Insureblocks). BigChainDB, Trent’s and Bruce’s start-up ran a project for MOBI to think about data sharing for machine learning for autonomous driving.

Chris also points out that every year pundits predict that this will be the year of autonomous driving with autonomous taxis taking us from A to B. Autonomous driving, because of all its edge cases is very difficult to do. The other autonomy problem is the ability for a car to participate in an economic transaction autonomously.

Chris believes that long before cars can drive autonomously they will be able to pay for things, pay for roads, pay for data and perhaps sell data to create real time maps. They will have the ability to trade data with cars around them and pay for pollution charge and perhaps get credit for carpooling or picking up passengers.

While the autonomy and driving is a really hard problem, the autonomous payments is basically sticking a profit function into a car, sticking a secure wallet and a secure identity into a car. It’s basically a question of agreeing on standards, not a question of massive advances in technology or in data collection.

MOBI’s role is in developing standards which could lead into creating this kind of autonomy and payments ecosystem relatively quickly which is hugely important for the industry and for smart cities.

Vehicles becoming autonomous economic agents

At a recent conference Chris stated that there was an opportunity for autonomous cars to becoming mini weather stations through their windshield wipers. Today’s modern cars have rain sensors which automatically activate the windshields wipers. Those sensors could also be used to act as mini weather stations. This is part of a more general point, the combination of identity, sensors and connections with a vehicle wallet will allow the car to monetize itself through the buying and selling of data.

Chris believes that in the not so distant future, vehicles are going to be programmed to make a living off their environment by maximising the amount of data that they can sell as a way of reducing their cost of operation. Buying and selling of data is likely to be a multi-billion dollar business over the next 10 years

MOBI’s working groups

MOBI operates primarily through its working groups. A working group is essentially built around a use case where a standard is needed.

The very first working group was around vehicle identity because without a secure identity you can attribute anything.

The second working group is around usage-based insurance. Once that vehicle is connected with an identity you can have a very different type of insurance that exists today. An insurance that is based on who the driver is, characteristics of the driver, time of the day the vehicle is driving as accidents become more or less probable depending on time of the day. Having access to the location of the vehicle is an important fact as some parts of cities are more dangerous than others. The more data you can access that is relevant to the underwriting liability the move valuable this becomes for insurance companies who have to underwrite this risk.

The third working group is on electrical vehicles and grid integration. The problem about the existing electricity grid is that it’s very top down. With electric cars plugging in, it is going to become much more important to get information from the bottom to the top. Kind of a distributed information processing problem. For example, if too many electric cars plug in at the same time in a same block the have the potential to bring down a portion of the grid. On the other hand, they also provide storage capacity for the grid to help even the load. This is also known as “vehicle to grid’ technology. Auto Car reported on how the French car manufacturer, Renault ran a pilot scheme in the Dutch city of Utrecht, where they used their electrical car, Zoe to prove the feasibility of vehicle-to-grid charging systems.

The fourth working group is on data marketplaces for connected vehicles, that is based on the work that the co-founders of Ocean Protocol are working on.

The fifth working group recently started which is on supply chain management. The sixth working group is on finance securitization and smart contracts.

Vehicle identity

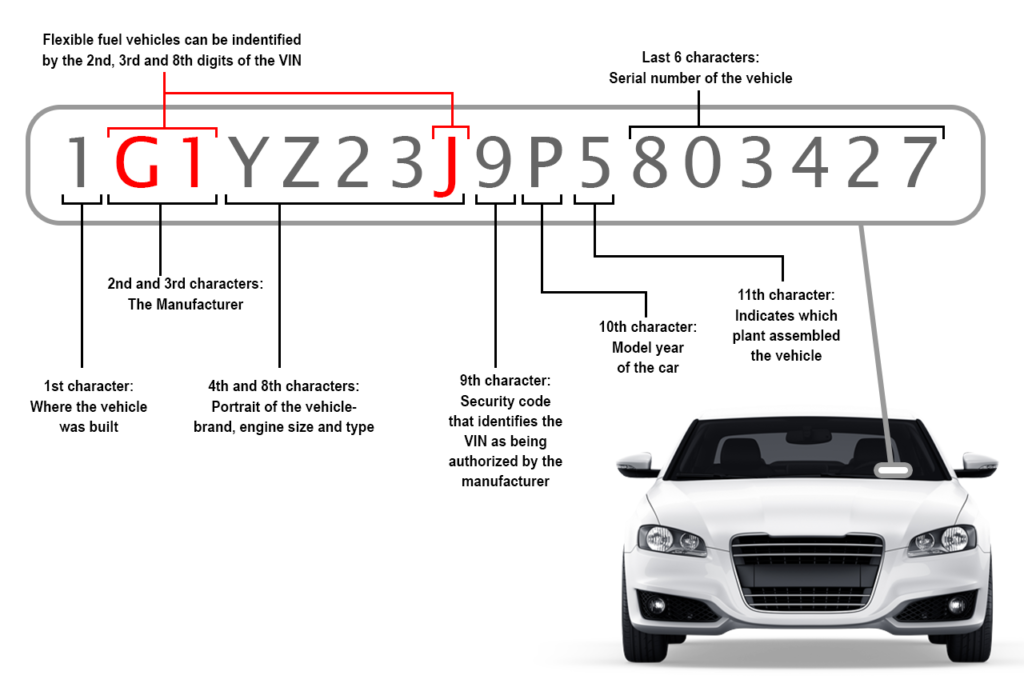

Vehicles today have a vehicle identification number also known as a VIN. That VIN operates in the physical world. In order to create a digital twin for the VIN and make it more useful it needs to be coupled with additional information. The more information it has the more useful that digital identity becomes.

There is a lot more to identity than a number. For example, when somebody asks, who Chris or who is Walid, they don’t just want to see a copy of our birth certificate, they want to know, who you are and where do you live? They may also want to know, where do you go to school, what your capabilities are, what you’re good and whether you are a good guy and trustworthy amongst many other things.

MOBI took the same approach for the vehicle identity. It has a birth certificate, information about the vehicle, who has the right to create the original record and how does the original record get rated in a way that can be trusted by others within the ecosystem. It’s a combination of useful attributes and who has the rights to specify the original record that constitutes the vehicle identity.

The vehicle identity project has two more additional phases. The first phase was on the vehicle as it leaves the factory. The second phase is focused on how you incorporate all the events that happen in a vehicle’s life after it leaves the factory. For example, how many miles has it driven, how was it serviced, did it have certified parts or counterfeit parts installed? Was the vehicle involved in a serious accident or not? Essentially all the kind of information that has an impact on the vehicle’s value once it has left the factory.

Chris states there’s also the opportunity to think of the supply chain to tracing the provenance of all the parts that go into the vehicle. Adding that component to the other two aforementioned phases will create a digital identity of the vehicle from the cradle to the grave. That secure identity can also act as an autonomous agent through the selling of buying of its data. You can have reputation scores and reputation values appended to it.

Supply chain working group

This is one of the newer working groups which is being chaired by Ford and BMW. Supply chain within the automotive industry is known as being one of the most complex there is. Car manufacturers have to keep track of about 50,000 parts or more. Through the course of assembly there will be numerous parties involved with parts coming from up to three tiers of suppliers. The capital markets that support the supply chain are themselves very inefficient with the payments that goes the reverse way forming a mirror image of the production process.

On both sides of that physical supply chain and the capital supply chain there are extreme inefficiencies. The processes are paper based generating enormous amount of waste. The suppliers tend to be shared amongst the automakers so there’s an enormous potential for automakers to get together and standardise information on the blockchain. To have secure identity for car parts and have information and data that can be shared amongst the players within the ecosystem.

Chris had great respect for the Daimler’s “Mobility Blockchain Platform” (MBP) hardware car wallet solution. However, he pointed out that they would have to face the great challenge of scaling and the additional problem of convincing their competitors to join their platform. Coming onto a competitor’s platform involves a number of competitive and strategic risks.

MOBI Grand Challenge

Similarly to the DARPA Grand Challenge, MOBI launched its own Grand Challenge. The first grand challenge was pretty open as the only requirement was to bring something interesting that was done on the blockchain that involved mobility. Most of the entries involved vehicle to vehicle coordination. There were entries that showed how vehicles could coordinate with other vehicles autonomously. There were platooning solutions and solutions that reduce congestion.

The second challenge was more focused on incentives on people for better, greener, smarter city behaviour and urban mobility behaviour.

The issue of governance

Chris recognises that governance is a really big issue in the blockchain world. The corporate world has had 300 or 400 years to work on corporate governance. So, it’s not surprising that in the blockchain world, especially where large amounts of money are raised, suddenly the stakes are very high. MOBI is a non-profit, so there isn’t a big pot of cash to fight over. The biggest problem with governance is diminished but it is still an issue.

The real governance question is, is how do you build a community in an ecosystem of competitors. MOBI did it by finding the people in the mobility industry who were passionate about the technology. These are the people who were giving their kids allowances in Ether or had run a blockchain proof of concept for a car share programme within the bowels of their company.

What helps MOBI is that they have full time staff which aren’t distracted by their day jobs. This ensures that MOBI is able to show demonstrable progress, that standards are coming out and they’re running PoCs at scale. They are demonstrating to their partners that they can run their R&Ds more effectively as part of a group at lower costs than doing them on their own.

Top tips for consortiums

Chris had a set of top tips for any aspiring consortiums. Run the consortium as a non-profit as a for profit consortium may generate suspicions with the members and they may become more reluctant to join.

Have full time people working on the consortium to ensure focus. Have the members pay up their dues to support the costs of running the consortium. To do that the consortium needs to produce a credible vision of where it’s going and why it’s important. How it creates a competitive advantage that is defensible in their relevant industry. Finally ensure that there is enough expertise from within the industry, especially when it comes down to writing standards.

What’s exciting about the next few years?

What excites Chris about the new few years is vehicles equipped with an ID and a wallet, with the ability to pay for things as it goes, is going to open up enormous possibilities for better mobility and for better cities.

Paying for infrastructure as you go. An onboard wallet and a trusted identity for the vehicle suddenly allows a congestion pricing in the inner city. It could allow city managers to deal with some of the most intractable problems of urban mobility such as congestion, pollution and carbon footprint to name a few.

Creating incentives for people to avoid certain areas at certain times of the day. Real time congestion pricing, creating incentives for people to take public transportation, creating the ability to do multimodal trips with an app that can protect data. An app that can protect identity and make micro payments and have a payment gateway that flows all the way through the app to various service providers. These are all things that the technology and vehicle wallets can open up that hadn’t been possible before.

The reason why this is particularly exciting for Chris is that the technology is here. It’s largely a matter of standards and adoption agreement to move forward. It’s about getting the community together, running a few trials with cities and government agencies to show it can be done. And then it is building it out at scale.